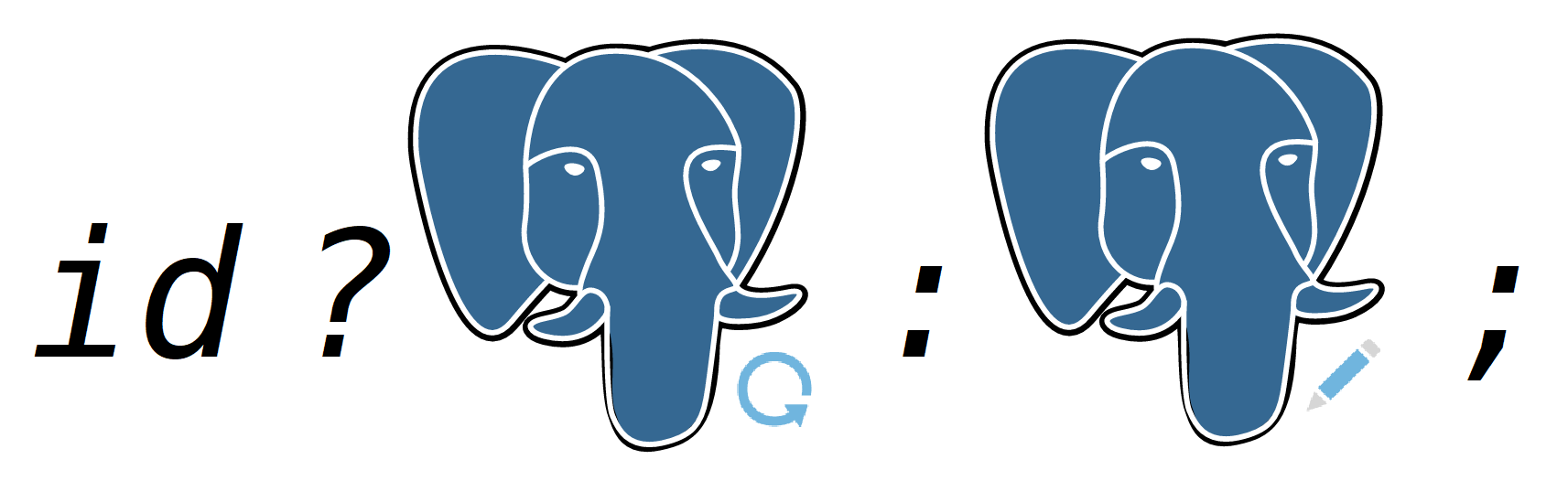

Upsert in PostgreSql using Knex

What is an upsert, anyway?

An upsert is short for “update or insert” in the context of SQL statements for databases.

The typical use case for an upsert, is when you have some data that needs to be in a row, but you are not sure if that row already exists - based on its primary key - then you would need to either insert a new row, or update the existing row.

However, upsert is not a command that was part of the SQL '99 standard, and therefore many database vendors either do not support it, or if they do support it, the query syntax for it can vary significantly 0 .

Sans explicit upsert support permalink

If you wish to perform an “insert or update” in a scenario that is similar to the one described above, but the database that you are using does not support it, with some difficulty, you can achieve the same thing.

If, based on your application domain, inserts are more common than updates:

- Perform an insert

- If the insert failed because primary key already exists, perform an update

- Wrap the above in a transaction, so that the operation remains atomic

Otherwise, if updates are more common than inserts:

- Perform an update

- If the update failed because primary key does not exist, perform an insert

- Wrap the above in a transaction, so that the operation remains atomic

Both of the above are the same, except for the order in which the insert and update operations are attempted.

Upsert in PostgreSql permalink

Postgres landed support for upsert in 9.5, so thankfully one does not need to deal with the above. They do not name it upsert though, instead it is done via an insert statement that uses an on conflict clause. An excerpt from the documentation:

ON CONFLICT DO UPDATE guarantees an atomic INSERT or UPDATE outcome; provided there is no independent error, one of those two outcomes is guaranteed, even under high concurrency. This is also known as UPSERT — “UPDATE or INSERT”.

Knex raw statements permalink

Knex is a NodeJs database library which performs 3 key functions:

- Query building

- Migrations

- Connection and pool management

It is, however, important to stress that it is not an Object-Relational Mapping library, even though most ORMs typically provide these functions too. 1

Knex supports multiple database vendors, including PostgreSql. Therefore when using its query builder, it only supports the commands that all of them have in common. This usually means anything that is part of SQL '99. Therefore, upsert does not make the cut.

Thankfully, however, Knex does provide an “escape hatch” of sorts, via knex.raw(): which allows you to write raw SQL 2. Forewarned, let us proceed to write a PostgreSql-specific command in Knex, which does an upsert.

Some readers out there might take it even further, and think, if we are using raw statements, why use Knex at all - why not interface with the database driver directly? We use Knex here mainly for the migrations and connection pooling which comes out of the box, and the query building is a nice-to-have which we might as well use. That being said, if you are already doing connection pooling and database migrations by interfacing directly with the database driver, or some other means, simply extract the SQL parts out in the following segments for the same effect.

Example of Upsert in Knex permalink

In the application I have been working on, an upsert was needed to insert or update rows in an account table. This account table consisted of only 2 columns:

idas astring, which is the primary key.bodyas ajsonb, which is for the rest of the account data 3.

knex.raw(

`insert into account ( id, body ) as original

values ( :id, :body::jsonb )

on conflict ( id ) do update

set body = jsonb_merge_recurse ( original.body::jsonb, excluded.body::jsonb )

returning *`,

{ id, body }

)Let us break this statement down, into its constituent parts:

knex.raw(sqlStatement, { id, body })This is Knex’ way of using named parameters - it substitutes in the values of id and body where :id and :body are present in sqlStatement. When Knex parses this, it transforms this into $1 and $2 in the SQL string passed to PostgreSql, so that you get proper parameterised queries. Do not use ES6 string templates - or any other equivalent method - to substitute the values in manually, because that would leave this query vulnerable to SQL injection attacks.

insert into account ( id, body ) as original

values( :id, :body::jsonb )This is a standard insert statement. The alias part (as original) is needed here to reference the current value in the table row, where it currently exists. You can name this what you want of course (does not have to be original), so long as it matches the usage in the following parts of the statement.

The next segment turns it into an upsert.

on conflict ( id ) do updateThe on conflict clause flags that this insert statement is actually an upsert, and therefore that it should check whether id already exists in one of the rows in the account table. If it exists, it will attempt an update instead of an insert. When defined in this manner, during query execution, PostgreSql does not need to attempt an insert and if a failure occurs, subsequently attempt an update, as the literal reading of the query string syntax might imply. Instead, it would need to do an index lookup on the primary key (id), then know immediately which of insert or update needs to happen.

set body = jsonb_merge_recurse ( original.body::jsonb, excluded.body::jsonb )Here we are updating the body as we would in a standard update statement. 4.

Of particular note, is excluded, which is a special keyword that refers to the new values in the row that would have been inserted if this had not become an update. This is mentioned in passing in the alias and conflict_action action sections of the on conflict section of PostgreSql’s documentation 5.

original is the alias which we defined earlier, and refers to the previous values in the row in the table which matches the id, as specified previously in on conflict ( id ). So the values are the values prior to this statement being executed. 6.

returning *In both update and insert statements, the returned output from the database is normally the number of rows that have been affected. In this case, we are always expecting this value to be 1, because:

- If there was no row with the specified

idbefore, there is a new one now - If there was an existing row with the specified

idbefore, the same one is still there

That is not very useful. Since it is an upsert, we care about what the new value for body in this particular one row is after the statement is executed. Therefore we use returning * to get the entire row back.

This is, of course, optional - if you do not need to use this information, and only care whether your query has succeeded or not, you can omit this, and shave off a few bytes of network traffic between the database and the server.

When you should use upserts permalink

If you have an action where the entity you need to write to may or may not already exist at that point. In other words, when the business logic of the application has no clear demarcation of separate operations for create and update operations, an upsert is the perfect use case for this.

If the database you are using provides built in support for upserts, it is certainly a great idea to use that instead of a hand rolled solution using separate update and insert statements wrapped in a transaction, for performance reasons. Not to mention that the database can provide a stronger guarantee of adherence to ACID principles than custom SQL transactions can.

Footnotes permalink

0 Support for upsert, or upsert-like, statements in various databases:

mergestatements are supported by Oracle, MS-Sql, and DB2insertstatements withon duplicate keyclauses are supported by MySqlinsertstatements withon conflictclauses are supported by PostgreSql and SQLite ↩

1 ORMs never seem to get it right. They either do not map relational table rows to objects closely enough, or they do at the expense of being extremely bloated. There is no Goldilocks amongst ORMs. In my experience, they usually seem like a good idea at the beginning of a project. They then transition, slowly but surely, to a source of technical debt towards later stages of a project. Knex, thus, occupies the sweet spot, by providing most of the bells and whistles that ship alongside ORM libraries, but skip automating the actual mapping or objects to relations. As a developer in the later stages of a project, chances are that you will find yourself wanting to write the mapping logic by hand anyway. ↩

2 When you do this, it is important to take note that this statement will likely not work on other databases. In practice, however, when switching databases, re-writing your queries is one of the least problematic tasks. In any case, it is a rare occurrence for any application to switch databases. ↩

3 This particular database table schema is designed to use PostgreSql as a document database, but that is a story for another post! ↩

4 Note that jsonb_merge_recurse is a custom PostgreSql function defined using create or replace function ...;, but that is a story for yet another post! ↩

5 There is room for improvement in explaining excluded properly, in PostgreSql’s documentation. There is also a target keyword mentioned here, but again, it is not clear from the documentation what this is for - it does not appear to be necessary for (this type of) upsert statements. This rather sparse documentation from PostgreSql was, in fact, the main motivation behind writing this post! ↩

5 A previous version of this post used excluded where original, in part, due to confusion over the on conflict section of PostgreSql’s documentation. Thanks to Ufuk Tandogan for pairing with me on this to figure it out - it was a particularly tricky issue to debug! ↩